Jon Savage. Image: Daniel Meadows (c) 1980.

There follows an article written by Jon Savage for Queer Noise/MDMArchive in 2010:

"Today, Manchester is barely recognisable from the city that I moved to thirty-one years ago, in spring 1979. I’d come from London so I knew it was going to be different, but nevertheless it was a culture shock: it felt like travelling back twenty years in time from the capital. Not that London was so fabulous then, but pre-regeneration Manchester felt really bleak.

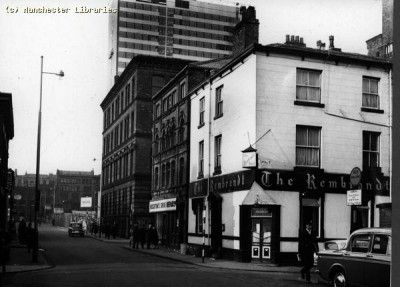

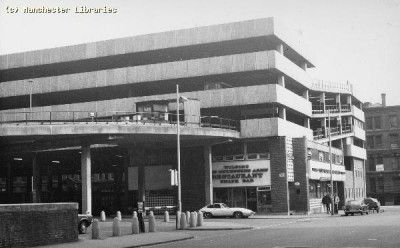

It was the depths of recession. There were huge areas of empty space: bomb-sites or large-scale demolitions for the redevelopment that had not yet occurred. The modern shopping centre – the Arndale, Market Street - was grey and soulless. The general atmosphere was oppressive, thanks to the aggressive policing of James Anderton, the chief cop sent by God to rule over the city.

Manchester felt under lock-down then: if you were out late at night, you’d get stopped at least twice a week. It wasn’t just gay people, it was anyone who looked and acted different. Anderton’s presence was ‘really malevolent’ as queer writer and DJ Liz Naylor remembers: ‘I think he really did look around the city and thought “this place is full of scum and I’m going to wipe it out”.’

It was not a happy time or place, in retrospect. I’m glad to see that there are accounts of gay people having a good time and living well during this period, but that wasn’t the case for me. I was still uneasy about being gay: tentative, prickly, feeling barely fit for human consumption. This is a common experience for many people in the same position today.

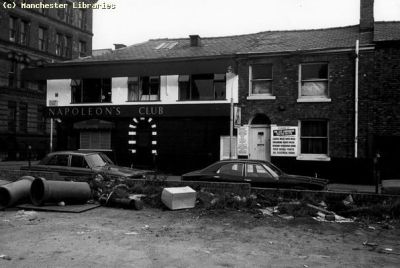

I didn’t identify with the then commercial gay subculture. There were clubs like Hero’s but I didn’t like Disco then – more fool me – and I didn’t associate sex with drinking, so it was a bit pointless. I couldn’t make it work. While absurdly over-dramatising in its conclusion (I didn’t go home and ‘cry and want to die’), the Smiths’ “How Soon Is Now” captured that experience well.

My work-mates at Granada, where you would have thought tolerance would prevail, weren’t that helpful. Gay people were clustered in Light Entertainment – a form of TV that I disdained – and they were bewildered by my lack of interest in their subculture. ‘Why don’t you dress like us’, they asked me: well, I didn’t like pastels, Kickers or Fiorucci. I was a punk rocker, for god’s sake.

My social life was taken up by the people in and around Factory Records. The Manchester rock scene didn’t talk much about homosexuality, even though several leading lights were bisexual at least. Of the Factory trinity, Martin Hannett simply didn’t care, Rob Gretton was surprisingly sympathetic and warm, Tony Wilson not so – an attitude that eventually caused a divide between us.

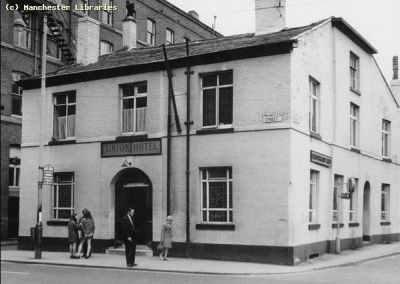

I began to sense a big injustice and got interested in gay rights. You could buy a range of pamphlets and books in the large, subterranean Grassroots that was just off Piccadilly. There was also a Manchester Gay Centre on Oxford Road – but it all seemed small and fragile, a shard of hope in the face of a public attitude that veered between tacit contempt and active harassment.

It felt like the dark ages and we were in the shadow. I was rescued by Tony Warren, with whom I briefly worked on a project called “Love Margox” – a vehicle for GTV presenter Margi Clarke. In retrospect, this pilot – filmed in early 1980 – was a non-stop, over-the-top camp-fest, with contributions from Carol Ann Duffy, April Ashley, George Melly, Frank Clarke and Tony Warren.

Perhaps it was too ripe for the Granada bosses, because it was cancelled. Tony took pity on me – in retrospect I was pretty hopeless – and we’d go to the Granada Bar, the Stables, and talk about the Sixties, in particular the music scene and Brian Epstein. Tony had worked on the Gerry and the Pacemakers film “Ferry Cross the Mersey” and regaled me with stories secret and scurrilous.

Eventually he told me about the gay sauna that was beneath the Brooklyn Hotel on Upper Chorlton Road in Whalley Range. So I went – it was on my way home - and my life was changed. It was the period just before AIDS, around 1980/81, and in the steam bath and sauna many of my hang-ups began to dissolve. No lasting relationships resulted, but I had a pretty good, guilt-free time.

There were other saunas during that period: in particular the Euro Sauna in Stretford, which later moved to Blackley, on the edge of a tough housing estate – I think it later burned down. The Brooklyn became Stallions, and lasted well into the 90s before being torn down for redevelopment: there should be a plaque there to record for posterity all the orgiastic behaviour.

I left Manchester at the end of 1982. In retrospect, I value the warmth and friendliness I received from many gay men during that period. I’m also very glad that gay people in the city can live with freedoms barely conceivable thirty years ago, indeed that they have emerged from the dark ages imposed by those who would oppress in the name of the light. That’s the best revenge of all."

Queer Noise: The History of LGBT+ Music and Club Culture in Manchester.

Queer Noise: The History of LGBT+ Music and Club Culture in Manchester.